The core decision between a Roth and Traditional IRA hinges on comparing your current marginal tax rate with your expected future effective tax rate. Your marginal tax rate matters for savings, as each dollar saved in a traditional IRA is sheltered from your current marginal tax rate. But during retirement, what matters is the effective tax rate. Given the increases in the standard deduction for tax year 2018, your effective tax rate is likely lower than you are assuming when comparing the two options. This makes the Roth IRA more attractive than it should.

This post focuses on the tax rate difference on withdrawals between Roth vs Traditional IRAs. It does not consider other factors such as estate planning, Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs), loans, or other considerations not related to the tax rate difference on withdrawals of the two options.

The Simple Comparison

Before we get into the details of our argument, let's look at a typical simple comparison of Roth vs. Traditional IRAs.

Assumptions: 25% tax rate now and in retirement. You have $7,500 cash in hand to invest.

| Step | Roth IRA | Traditional IRA |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Invest | You put the $7,500 directly into a Roth. | You put $10,000 into a Traditional IRA. (This "costs" you $7,500 because your tax bill is reduced by $2,500). |

| 2. Growth | Your $7,500 doubles to $15,000. | Your $10,000 doubles to $20,000. |

| 3. Tax | You withdraw $15,000 tax-free. | You withdraw $20,000 and pay 25% tax ($5,000). You keep $15,000. |

| Result | $15,000 Spendable | $15,000 Spendable |

In a simple example like this, the two options are equivalent. As long as the current and future tax rates are the same, it does not matter which option you choose. It is your assumption of current vs future tax rates that is the decision maker

Historically, personal exemptions and standard deductions were lower than they are today. Further, many people would work late in life, and have Social Security, a pension, or both. This simple math worked reasonably well.

However, today's reality is more complex given large standard deductions, the lack of pensions, and the desire of the FIRE community to retire early (prior to any Social Security). With no other income sources, the difference between marginal and effective tax rates is much more pronounced.

U.S. Taxes - A Primer on Marginal and Effective Tax Rates

In the U.S. tax system, there are different tax brackets depending on filing status: married filing jointly (MFJ), married filing separately (MFS), head of household (HOH), and single (S). Each filing status has its own tax brackets. For the rest of this article we will focus on single filers, and married filing jointly, as they are the most common filing statuses. The general concepts apply to all filing statuses.

The U.S. tax system is a progressive tax system, meaning that the tax rate increases as the taxable income increases. People frequently call the highest rate of tax they pay on income their "tax bracket", but this is not accurate. The tax bracket is the range of taxable income that is subject to a specific tax rate.

- Marginal tax rate - The tax rate a person pays on the next dollar of income. It is more accurate for a person to state their "marginal tax rate", which is the highest rate of tax they pay on income.

- Effective tax rate - The effective, or average, tax rate paid on taxable income. It is the total tax paid divided by the taxable income.

In summary, the marginal tax rate is the tax rate a person pays on the next dollar of income, while the effective tax rate is the average tax rate paid on taxable income. Since the tax system is progressive (made up by paying sequentially higher percentages of income as income increases), the marginal tax rate is always higher than the effective tax rate.

Standard Deduction

Another concept to understand is the standard deduction. The standard deduction is a fixed amount of taxable income that is not taxed. For tax year 2025 the standard deduction is $15,000 for a single filer and $30,000 for a married filing jointly. This means a single filer reduces income by $15,000, and a married filing jointly reduces income by $30,000, before calculating their tax liability.

The standard deduction has the effect of reducing effective tax rates. I.E. The 24% marginal tax bracket starts at $103,350 for a single filer, but that $103,350 is after reducing your income by the $15,000 standard deduction. So you would need to earn $118,350 to be in the 24% marginal tax bracket.

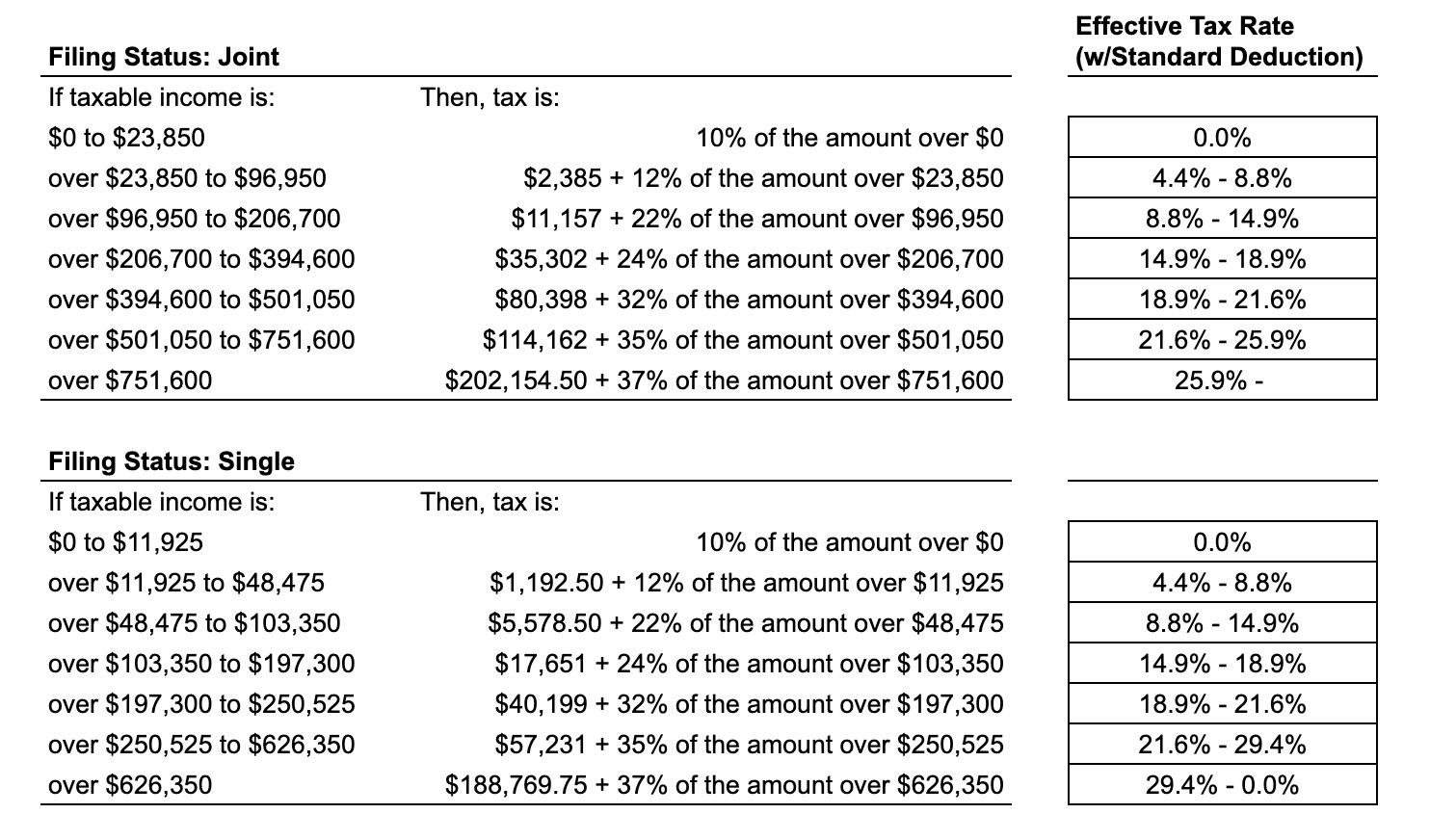

The tables above show tax year 2025 tax brackets, marginal tax rates, and effective tax rates for joint and single filers. (These rates were taken from Congress.gov)

The marginal rate is the value in the table just prior to "of the amount over".

The effective tax rates are shown for all taxable incomes up to $626,350 (single filer) and 751,600 (married filing jointly).

Takeaway: The effective tax rate is between 37% and 84% of the marginal tax rate for incomes up to $626,350 (single filer) and 751,600 (married filing jointly). (As income goes to infinity, the effective tax rate approaches 100% of the marginal tax rate.)

Example - Single Filer, 2025 Tax Year

Let's look at an example of how to calculate the marginal and effective tax rates for a single filer with taxable income of $115,000.

First, calculate Adjusted Gross Income (AGI): $115,000 - $15,000 = $100,000

Next, find the marginal tax rate. In this case, $100,000 is "over $48,475 to $103,350", and thus the marginal tax rate is 22%.

Calculate Tax: $5,578.5 + 22% of ($100,000 - $48,475) = $16,914

The marginal tax rate is 22%, while the effective tax rate is 14.7%, calculated as: $16,914 / $115,000.

Why Effective Tax Rate Matters for Retirement

The core argument is that the tradeoff is between paying your marginal tax rate now on money that goes into a Roth IRA, OR paying no tax now on money that goes into a Traditional IRA and paying your effective tax rate in retirement.

- Savings (Now): Every dollar put into a traditional IRA reduces your taxable income from the "top-down," meaning you save at your highest current marginal bracket.

- Withdrawals (Future): When you withdraw from a traditional IRA in retirement, those dollars fill your future tax brackets from the "bottom-up." The first several thousand dollars are untaxed due to the standard deduction, and the next portions are taxed at the lowest rates (e.g., 10% or 12%).

- The "Effective" Reality: Because your future dollars benefit from these lower tiers, the "cost" to withdraw those funds is indeed your effective tax rate on those specific withdrawals, which is significantly lower than your current marginal rate.

Let's assume this hypothetical single filer saved enough to have the same income in retirement as they did when saving ($115,000). (We always use real dollars; inflation adjusted to keep purchasing power constant.) Assuming a withdrawal rate of 5%, this single filer would need to have saved $2,300,000.

Given the same income in retirement as during savings, our hypothetical single filer can either pay a 22% rate on their savings now and 0% tax on withdrawals in retirement (Roth IRA), or pay no tax now and 14.7% tax on withdrawals in retirement (Traditional IRA). Clearly, paying 14.7% tax is better than paying 22% tax. For this example, an income of $274,637 would be required in order to pay the same effective tax in retirement as the marginal rate during savings.

Could Our Hypothetical Single Filer Save Enough to Have Retirement Income of $115,000?

Assuming a withdrawal rate of 5%, our hypothetical single filer would need to have saved $2,300,000 to generate $115,000 in retirement income. ($2,300,000 * 5% = $115,000)

- To have $2.3M in retirement would require saving roughly $21,000 per year, increasing savings at 3% per year (real - above inflation), for 30 years, and assuming 7% real returns on savings.

- For someone with $115,000 income, that savings is probably unrealistically high.

- If your thinking that savings is reasonable because "I'll be making more in the future and saving will be easier", then you need to read our post on that subject.

- To have $274K of taxable income in retirement, our hypothetical single filer would need to save $4.5M. (Total income - Social Security benefit = $274,000 - $48,216 = $225,784. At a 5% withdrawal rate, $225,784 / 5% = $4,515,680). The annual savings required would be about $40K, which is entirely unrealistic for someone with $115K of income.

Would Social Security Fill the Lower Buckets?

For 2025 the maximum Social Security benefit for someone claiming their benefit when reaching full retirement is $48,216. For joint filers, where only one spouse worked, the maximum benefit, claimed at full retirement age, is $72,234.

- Adding $48K to our hypothetical single filer's $115K retirement income results in total income of $163K; well below the $274K needed to pay the same effective tax in retirement as the marginal rate during savings.

The Problem with the "Effective Tax Rate" Argument

The potential flaw in this argument was mentioned in the The Simple Comparison section above.

This argument assumes your taxable income in retirement will all be coming from your Traditional IRA. However, if you have a pension, Social Security, or other sources of income in retirement, those will boost your income. Your Traditional IRA withdrawals will be taxed at the marginal tax rate after those other sources of income are accounted for.

Social Security alone will not increase the taxable income enough to offset the lower effective tax rate. But if you expect to have a pension, a significant inheritance, or other sources of income in retirement, then the effective tax rate argument may not hold.

Will Taxes Go Up or Down in the Future?

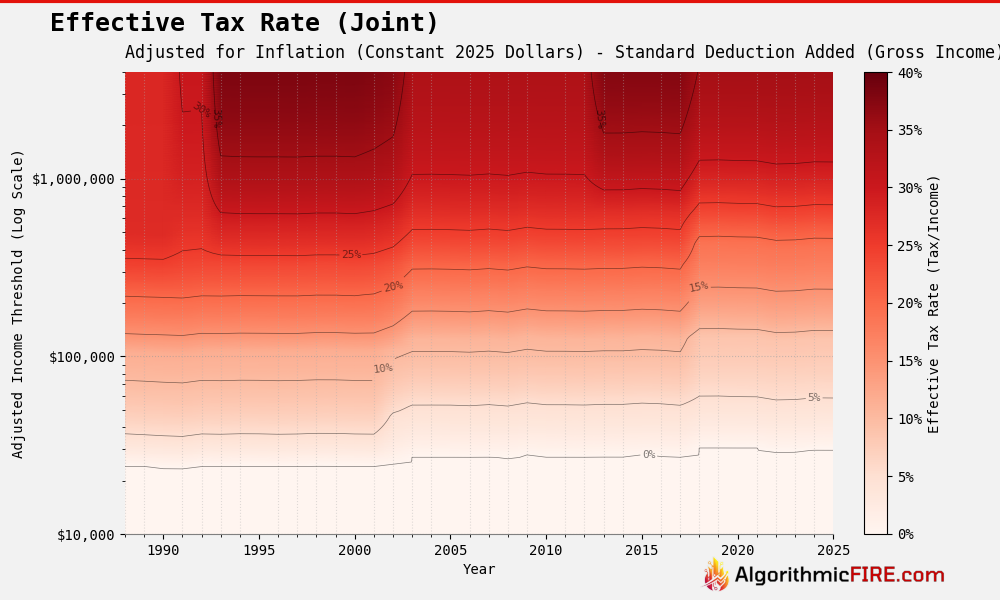

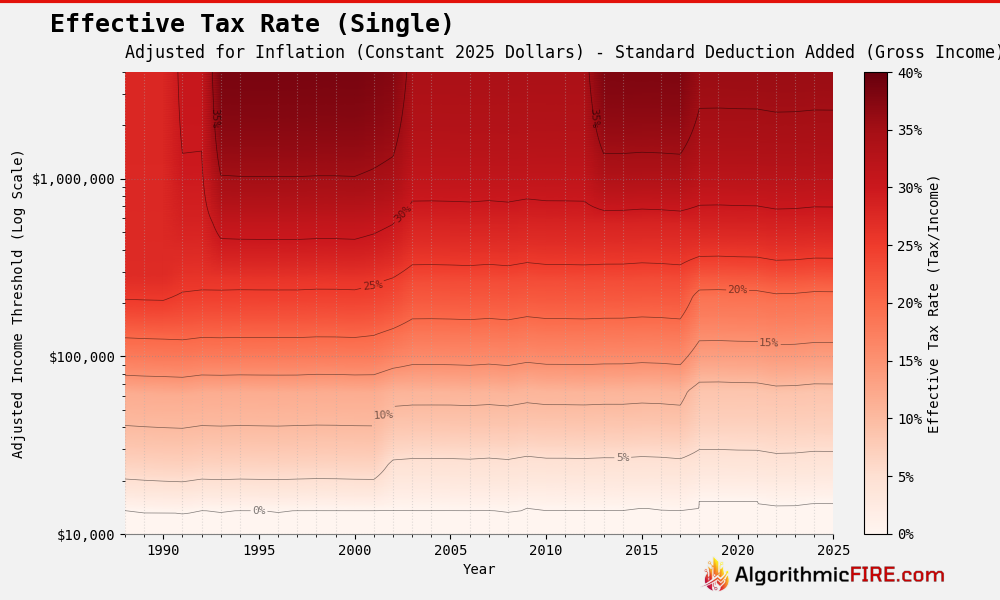

Higher future personal income tax rates are also possible, and those favor a Roth IRA. But for decades the supposition has been that personal income tax rates will go up in the future. So let's look at how they've changed in recent history.

The charts above show the effective personal income tax rate, adjusted for inflation, for single and joint filers from 1988 to 2025. Note that effective tax rates have been relatively stable over this period. If anything, rates for incomes over $100,000 have declined over this period. (Contour lines, showing constant effective tax rates, are shown in black and generally only move upward, indicating it takes more income to achieve the same effective tax rate over time.)

It is important to keep in mind that the government can also raise revenue from: corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, estate taxes, tariffs, and other sources of revenue. Raising personal income taxes is not the only way to raise revenue.

Takeaways

- For our hypothetical single filer with $115K income, with the same income during both the savings and retirement periods, the taxes paid using a Roth IRA are 22% versus 14.7% using a Traditional IRA.

- Social Security income does not increase the taxable income enough to offset the lower effective tax rate.

- To save enough money to have the same taxable income in retirement as during savings requires a relatively high savings rate. Saving enough to get the marginal tax rate during savings to equal the effective tax rate in retirement is unrealistic.

- If you expect to have a pension, a significant inheritance, or other sources of income in retirement, then the effective tax rate argument may not hold.

Tax issues are complex. This post uses many simplifications and assumptions to make the argument clear regarding the effective tax rate argument. This post is meant to give you the information you need to start questioning the conventional wisdom regarding Roth vs Traditional IRAs. But your personal situation will not be the same as our hypothetical single filer. You need to understand your own personal situation before making any decisions. This post is not tax advice. Please consult a tax professional before making any decisions.

Ready to learn more?

See a list of recent blogs on our home page.

Or, dive deeper into investing, saving, and withdrawal strategies through our comprehensive Curriculum.

Subscribe now to get:

- Our new blogs delivered straight to you via email.

- Access to all historical blogs. (Only recent posts are availble to non-subscribers.)

- Access to videos and all of our calculators.

- Access to all blog content as a downloadable PDF.

- Access to our Dashboard with trend following results.

Thanks for reading! Feel free to share this post, and follow us on social media:

Disclaimer

**For Educational Purposes Only:** All content on this site, including articles, tools, and simulations, is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be construed as financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. The information provided is general in nature and not tailored to any individual’s specific circumstances.

**Software Development Has Inherent Risks:** The software used to perform the analyses may have errors or inaccuracies. When we post updates to any material, errors or inaccuracies that are subsequently fixed may change the results.

**No Guarantees & Risk of Loss:** The analyses and simulations presented are based on historical data. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future results. All investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Market conditions are subject to change, and the future may not resemble the past.

**No Fiduciary Relationship:** Your use of this information does not create a fiduciary or professional advisory relationship. We are not acting as your financial advisor.

**Consult a Professional:** You should always conduct your own research and due diligence. Before making any financial decisions, it is essential to consult with a qualified and licensed financial professional who can assess your individual situation and objectives. We disclaim any liability for actions taken or not taken based on the content of this site.

* Nobody associated with Algorithmic Fire LLC has any credential(s) or affiliation(s) with any licensing or regulatory bodies, including but not limited to: Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

© 2025-2026 Algorithmic Fire LLC. All rights reserved.